Share

Linguistic affinity and shared cultural background have historically been determining factors in Brazilian migrants’ decision to choose Portugal as their main destination in Europe. However, in the past ten years, due to citizenship liberalization and easy access to work, residence, and study visas, Portugal has attracted an unprecedented number of Brazilians.`

In this article, you will find an overview of Brazilian migration towards Portugal and its consequences in politics and society.

Facilitated Brazilian migration

Subtitle: Brazilian President, Lula, and Portuguese Prime-Minister, António Costa during a conference between the two countries. Credit: Ricardo Stuckert/PR

Post-colonial ties facilitated Portuguese residence access to several groups of citizens from Portuguese-speaking countries. Brazil and Portugal have fostered a particularly strong bond in several areas, including mobility. Since 2010, approximately 400 thousand Brazilians of Portuguese descent have been granted citizenship. Furthermore, since 2014, Brazil’s National Secondary Education Examination (known as Enem) is also valid for several Portuguese higher education institutions. Brazilians can also apply for a “Job Search” visa, which grants them up to 180 days to find work opportunities in Portugal.

However, another option for legal residence in the country was drawn to the spotlight last year: the Community of Portuguese Language Countries (CPLP) residence access. As a result of CPLP’s Mobility Agreement, this option grants citizens from any of the CPLP countries to reside in any of the member states, including Portugal, for up to three years. The Community defends that human mobility is one of the main ways to strengthen the ties between countries and that the visa would benefit its members. In addition, the obtention of this residence permit is particularly easy, for it is conducted fully online and requires almost no bureaucracy.

Although this visa favors the integration of CPLP member states, the mobility agreement is at risk. In September, the European Commission considered that Portugal failed to fulfill its obligations under the EU law. Therefore, the commission opened an infringement procedure concerning the CPLP Mobility Agreement.

In Portugal, the extreme right celebrates the EU’s decision.

Extreme-Right party Chega! grows

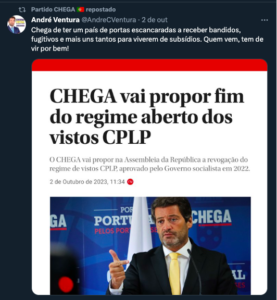

Subtitle:André Ventura, Chega’s president says “Enough of opening the country’s doors to receive criminals, fugitives and others to rely on social security. Whoever comes needs to have good intentions”. He retweets a news article on Chega’s position to end the CPLP mobility agreement.

The liberalization of residence in the country has bothered conservative and nationalist sectors of Portuguese society. This can be confirmed by the results of the two prior Parliament elections, in 2019 and 2022. Last year’s election was very positive for Chega!*, the Portuguese extreme-right party that now holds the parliament’s third biggest group. Although Portugal is currently ruled by a leftist government, the growth of nationalist ideology reflects social backlash to strengthening mobility with citizens from former colonies.

Not surprisingly, migration has gained special attention in Portuguese public debate and media. A central topic in Chega’s government agenda is to stop facilitated residence access to migrants, especially through the CPLP residence permit. This trend worries Portuguese-speaking migrants, particularly those who have been granted the visa – around 151 thousand people, most of them Brazilians.

While Portugal maintains its position to grant access to residence and citizenship, a growing wave of xenophobia scares migrant communities throughout Portugal.

Xenophobia and Discrimination against Brazilians

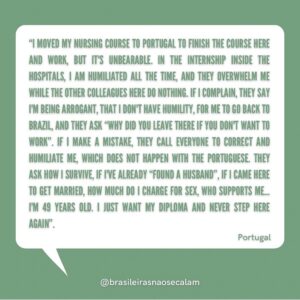

Subtitle: One of the hundreds of testimonies posted by online community “Brasileiras Não se Calam” (Brazilian Women won’t be Silenced, in English).

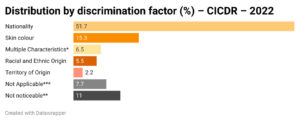

Portugal’s Commission for Equality and Against Racial Discrimination issued a 2022 report with data about the formal complaints the institution received regarding discrimination. More than half of the cases contained nationality as the primary factor for discrimination. Brazilians were the most affected, concentrating 34,2% of the cases.

Brazilians account for over 30% of the migrant population in the country. It is estimated that approximately 400 thousand Brazilians legally reside in Portugal. This makes them the biggest foreign group in the country and the biggest xenophobia target.

The idea that Brazilians are the root cause of many problems Portugal faces has created a dangerous atmosphere. Discrimination cases are numerous and to raise awareness about them, Mariana Braz, a Brazilian resident in Portugal, created the online community “Brasileiras não se calam” (Brazilian Women won’t be Silenced, in English). The online community collects testimonies from Brazilian migrants all over the world to show how discrimination affects these women and their families in receiving countries. The vast majority of the discrimination testimonies come from Brazilians residing in the former colonial metropole.

Although Portugal has a Commission to address these issues, Brazilian authorities worry that the country is not putting enough effort into tackling xenophobia. In April, Brazilian Racial Equality Promotion Minister, Anielle Franco, initiated talks with the European nation with the intent of fighting against discrimination and racism against Brazilians in Portugal.

If once this community praised the experience and encouraged others to migrate – creating a real immigration network – now social media is full of posts advising Brazilians against it or suggesting that Portugal can be rather a useful hub to access other European countries instead.

Portugal and Brazil share an intricate migration system. At the same time, the colonial past brings them closer in liberalizing policies among nations, it also serves as fuel for discrimination. The language, a clear heritage from colonization, for instance, serves as a social marker that separates Brazilians from Portuguese natives. The foreign accent led to physical violence against a Brazilian engineer who was at a café in the city of Braga. In June, a Portuguese passerby heard the migrant and instantly attacked him. According to a BBC article, such cases have led Portuguese-speaking migrants to use English when communicating with natives instead.

The growth of Chega’s political importance seems to legitimize discrimination and exclusion of migrant populations. Lastly, the inertness of Portuguese authorities in tackling hate speech against foreign populations leaves such communities powerless.

*In Portuguese, “Chega” can be used to demonstrate that one can’t accept a situation anymore. It expresses a negative reaction to something considered unbearable.