Share

The Musée National de l’Histoire de l’Immigration (National Museum of Immigration history) of France is at the center of a profound contradiction. Located in the 12th district of Paris, in the Art Deco Palais de la Porte Dorée (Golden Gate Palace), it was initially built in 1931 for the Colonial Exhibition held in Paris with the purpose to serve as a museum of the colonies, showing the history of colonial conquest and the impact of the colonies on the arts. Jacques Chirac’s government, after the 1998 World Cup, a moment when French people felt more united than ever, decided to approve the project of opening the actual museum, in order to “contribute to the recognition of the integration of immigrants into French society and advance views and attitudes on immigration in France.” In 2006, under Nicolas Sarkozy’s government, the Cité nationale de l’histoire de l’immigration was inaugurated. It officially became the Musée national de l’histoire de l’immigration in 2012, operating under the supervision of four ministries, Culture, National Education, Higher Education, and the Interior, because of its multidisciplinary mission.

This museum’s existence is very paradoxal; it tries to be a space contributing to the fair representation of minority identities by depicting immigration as a fundamental element of French national history while at the same time building those narratives on objects, testimonies and artworks collected and interpreted in france’s colonial past.

The structure of the exhibition

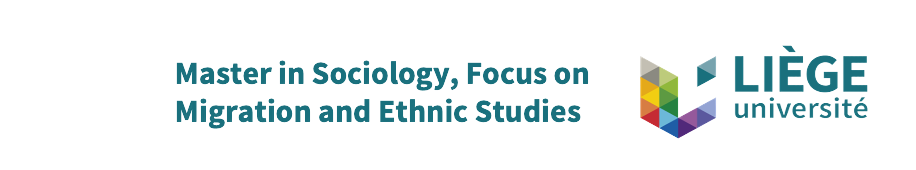

The exhibition is structured around 12 key sections, each corresponding to a specific timeframe, from the 1680s to the present day. Each section explores key historical moments and transitions in migration flows, migrants’ rights, and their treatment in France’s history. The exhibition moves through time, from slavery and its abolition to forced migration, colonization, wars, decolonization, 1970s activism, and the gradual construction of EU border policies. Each historical section includes summaries of migration policies and social contexts from that period, supported by archives, photographs, sculptures, digital tools (interactive maps and short documentaries), as well as testimonies and individual migrant stories. Every part of the exhibition focuses on portraying migrants as human beings, dedicating significant space to portraits and family histories.

In this way, the exhibition goes beyond historical facts and events, it insists on personal experiences and testimonies of forced migration, resilience, and solidarity across all periods it covers. The museum emphasizes that immigration is an essential part of France’s history and national identity.

The symbolic paradox

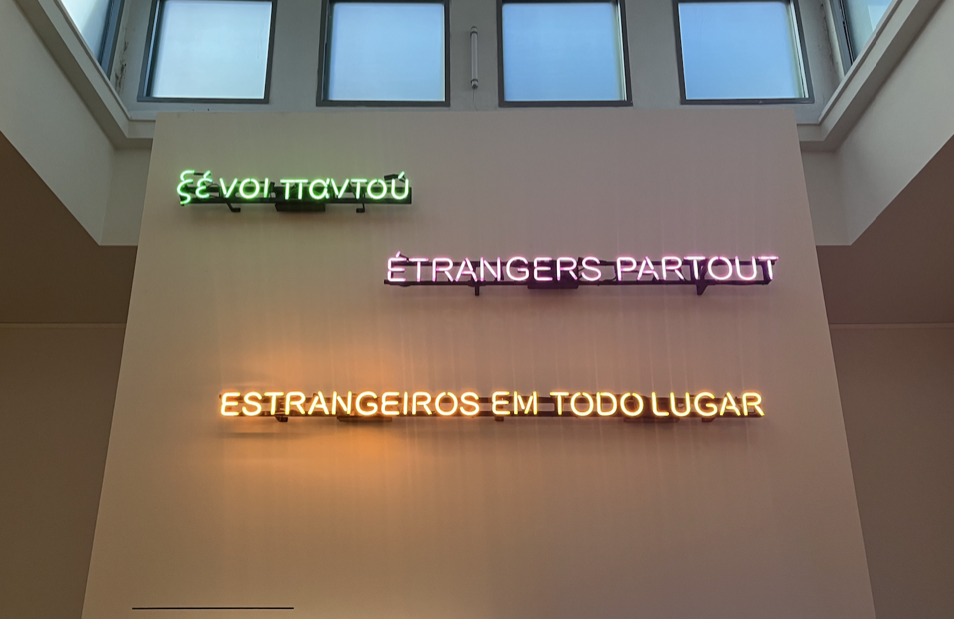

The National Museum of France’s History of Immigration illustrates a paradox: it seeks to equally represent minority identities while occupying a building filled with colonial history. It confronts visitors with colonial memory while promoting an inclusive version of history,

illustrating the difficulty of reconciling national identity with collective and personal memory. Some comments can be made on the approach used to construct the narrative of the exhibition.

The objects coming from France’s former colonies cannot be considered neutral; their presentation shapes the historical narrative. Here, the museum tries to go beyond a colonial prism by integrating these objects into the historical testimonies of immigrants, leaving us with a question: does this really fully convey the context of their acquisition, or does it unintentionally reproduce the dominant point of view from which it seeks to distance itself?

Personal narratives used in this exhibition are powerful tools that humanize history and place minority struggles at the center of the narrative. However, the selection and editing of these testimonies can be questioned, from the choice of narration to the resemblance between the migrants’ real experiences and what is presented in the museum.

In this way, the museum challenges visitors to reflect on how post-colonial societies can acknowledge their past while promoting migrant history and contributions to society. This museum attempts to be a space of mediation on France’s history and a tool for sparking conversation on the subject, while sometimes unintentionally maintaining mechanisms of colonization within the narrative presented throughout the museum.

Overall, this museum makes an attempt to transmit the history of migration in relation to France without avoiding difficult truths. It insists on telling history without sugarcoating, in a present context where colonialism and xenophobia remain sensitive and often avoided subjects in French history. During the two-hour visit, the amount of information can feel immense, yet visitors leave the museum with a global understanding of how immigrants have been treated throughout history, and a deeper comprehension of current migration issues. However, given the previous discussion on the paradoxical nature of the museum, visitors must maintain a critical lens while visiting and reading history as it is depicted in the museum. Nevertheless, the experience of Le Palais de la Porte Dorée leaves visitors with a sense of hope and optimism—that institutions like this exist and could shape future perspectives on migration and identity, even if their approach must be rethought and deconstructed. It is a powerful symbol to place a museum dedicated to migration and decolonization inside a building that once celebrated empire, but the gesture itself is not enough to decolonize its way of thinking and portraying history.