Share

Bad Bunny’s 6th album “DeBÍ TiRAR MáS FOToS” became ont of the most streamed album of 2025 by challenging mainstream trends, exploring Puerto Rico’s colonial status through a very personal project where he talks about his family, expresses identity and its loss, displacement, colonialism and gentrification.

Through his storytelling, “DeBÍ TiRAR MáS FOToS” became very impactful in the digital sphere; Internet users found meaning and identified themselves and their communities in the lyrics of songs, openly denouncing the systematic oppression of Puerto Rico by the United States of America. In what ways did this project manage to become a transnational site of digital resistance to modern-day colonization? In this context, we are building on postcolonial theories, to use the term colonization to describe a form of contemporary colonial dispossession and unequal power relationships, rather than giving it a strictly legal or historical status. This will allow our analysis of how political domination, cultural erasure and economic appropriation operate in the current world.

Music Across Borders

This album had a very big impact on digital platforms and social media, being reappropriated by other ethnic groups who identified themselves and their communities in Bad Bunny’s lyrics. On platforms like TikTok and Instagram, the Gazan community started a trend, creating “reels”, pairing the audio chorus of the song “DeBÍ TiRAR MáS FOToS” with photos and videos of their beloved city of Gaza before the beginning of its last wave of destruction and genocide in 2023. The lyrics of the song saying “Debí tirar más fotos de cuando te tuve” (I should’ve taken more pictures when I had you) and “ojalá que los mío’ nunca se muden” (I hope my people never move away), serve as carrier of nostalgic commemoration and a digital act of remembrance. This example shows us love and loss interpreted by transnational language of solidarity through which Gazans were able to articulate belonging, grief and resilience in the face of oppression. The song serves as a cultural artifact of global resistance, where the Puerto Rican experience voiced by the artist, colonization and modern history become a cross-border bridge into understanding diverse contexts of violence and erasure, serving as a tool of digital witnessing, evoking empathy and transmitting information.

This use of the song on social media platforms, shows how digital media can create and foster global solidarity by connecting different populations through common experiences. Music functions as a transnational narrative, allowing oppressed communities to share grief, resistance and memory, not only through digital engagement, but also through art.

In this way, Bad Bunny’s music enables transnational acts of resistance. We can contextualize this within the larger discourse in migration studies on digital colonization. While “data colonialism” wasconceptualized by scholars as a new form of extraction, converting human life into data streams for profit and control by the Global North; it is Martiniello’s work on ethnic minorities’ cultural and artistic practices as forms of political expression that shows us how resistance is enacted within this system. Marginalized communities are therefore able through the digital sphere, to articulate resistance, belonging, and grief, even through infrastructure controlled by powerful, mainly Western, companies. In the case of Gaza, these groups are seeking and reclaiming digital sovereignty, attempting to reappropriate and disrupt hegemonic online narratives, and by that to actively combat cultural erasure.

Denouncing the colony in the shadow of the U.S.

Puerto Rico’s history and present are largely defined by colonization and imposed economic dependency. In 1898, after the Spanish-American war, Spain ceded the island to the United States of America. This designated Puerto Ricans as U.S. citizens without full political representation; decisions over the island’s territory, economy and migration are currently outside of local control. This unequal power relationship was established through policies prioritizing U.S. corporate interests, and other laws (ex : law promoting individual American investors to purchase luxury properties in Puerto Rico), deepening inequalities, thus entrenching economic vulnerability.

Recently, tourism-driven gentrification in Puerto Rico has also become a problem, transforming public beaches into private properties, consequently displacing the population and threatening the cultural continuity of island life. Combining this economic appropriation with the political domination of the U.S. and the commodification of Puerto Rican land, we can talk about a form of contemporary colonial dispossession, where the island’s territory, identity and future remain precarious.

Bad Bunny’s album is a vocal condensation of the consequences this political system brings to the island and the feelings it produces. The song “LO QUE LE PASÓ A HAWAI’I” is the artist’s personal anthem against gentrification. Here is a part of the song’s lyrics and their translation:

Quieren quitarme el río y también la playa (They want to take my river and my beach too)

Quieren al barrio mío y que abuelita se vaya (They want my neighborhood and grandma to leave)

No, no suelte’ la bandera ni olvide’ el lelolai (No, don’t let go of the flag nor forget the lelolai)

Que no quiero que hagan contigo lo que le pasó a Hawái (‘Cause I don’t want them to do to you what

happened to Hawaii)

These lyrics describe feelings created by contemporary colonization, that the U.S. and tourism-gentrification are slowly stealing from the local identity. The singer is trying to urge listeners to hold on to that culture; “don’t forget the lelolai” insists on the importance of maintaining local culture, by referencing Puerto Rican folklore Christmas songs and lyrical chants used by traditional local singers. Referring to his grandmother in the chorus of the song, the artist symbolizes memory and tradition being pushed out, making a metaphor for cultural erasure. He then proceeds to make a comparison betweenthe United States’ treatment of Puerto Rico and Hawaii as colonial possessions, denouncing Hawaii’s military occupation, economic exploitation, displacement and cultural erasure by the U.S., bringing together both of the islands’ experiences.

In the song he also announces “No quería irse pa Orlando, pero el corrupto lo echó” (He didn’t want to go to Orlando, but the corrupt ones pushed him out). This line reflects how corruption and colonial dependency have forced locals into migration. Orlando is being referred to as a symbol of exile rather than an opportunity.

Bad Bunny’s political engagement beyond music

When announcing his 2025-26 world tour, Bad Bunny made the very political decision to skip mainland U.S. in his tour dates. By that, he made a statement; he won’t play in the mainland of the coloniser nor put the safety of his fans at risk, fearing that ICE would probably raid the venues where he would play. He also stated that “mainland America doesn’t feel necessary” to him anymore.

He also challenged Donald Trump in his “NUEVAYoL” music video, by parodying a radio announcement, imitating his voice and mocking him, announcing:

“I made a mistake, I want to apologize to the immigrants in America, I mean the United States. I know America is the whole continent. I want to say that this country is nothing without the immigrants. This country is nothing without Mexicans, Dominicans, Puerto Ricans, Colombians, Venezuelans, Cubans…”

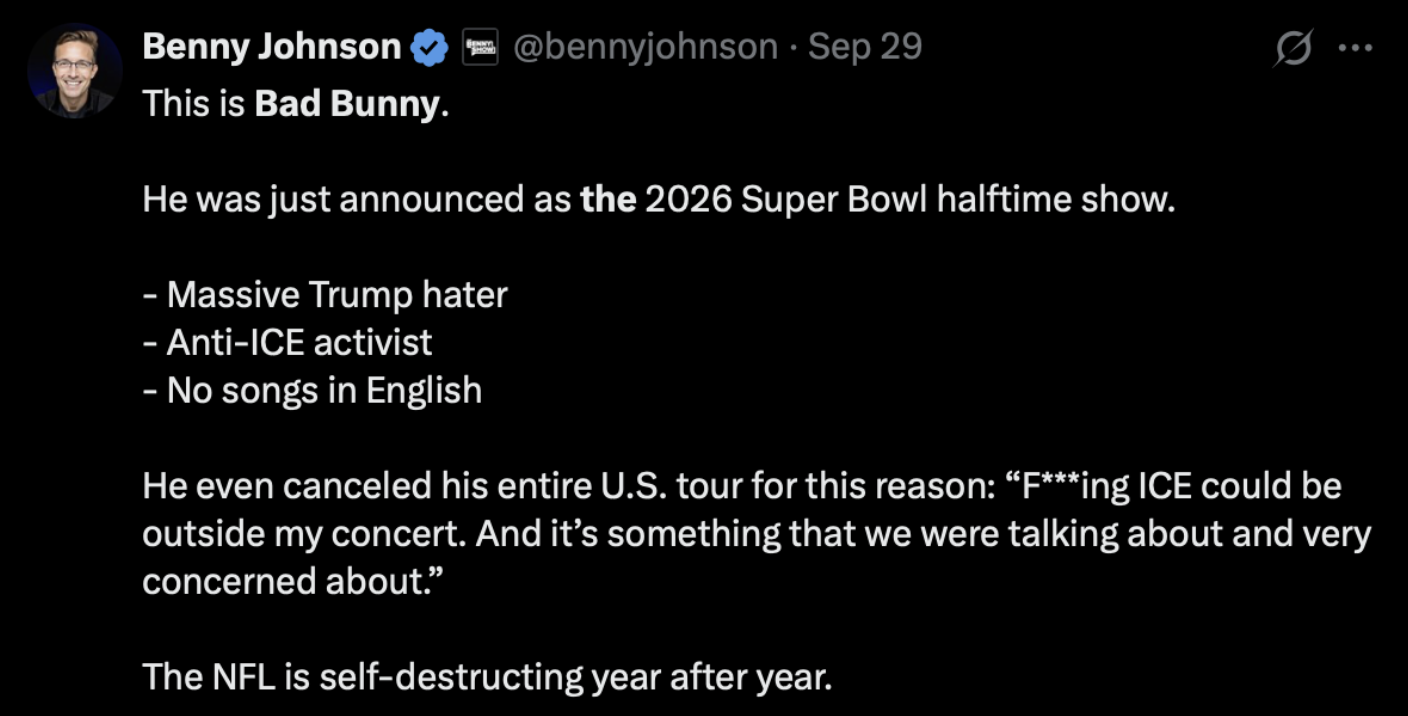

He then proceeds in the music video to stage himself on top of the Statue of Liberty displaying the Puerto Rican flag. Even though the artist is mocking the president and making substantial political statements, he still was chosen and announced by the NFL (National Football League) to play the half-time show of the 2026 Superbowl edition. This announcement had a huge mediatic impact and is extremely controversial mainly by MAGAs, considering that Bad Bunny sings exclusively in Spanish and that it should be “illegal” for Super Bowl performances. Some of the controversies seen were being discriminatory, verbalizing that he isn’t “American”, completely ignoring that Puerto Ricans are U.S. citizens. Here is a post on X criticising the announcement:

The NFL’s choice became so controversial that it sparked a boycott call, making the NFL’s commissioner, Roger Goodell, feel the need to make a public statement, saying that he is not reconsidering the halftim Super Bowl performer, despite the controversy.

We can see here that what begins as another mundane album from a world-class music artist, transforms into a platform using the narrative power of popular culture to express solidarity across all colonized and displaced communities. This project’s critique is reinforced by Bad Bunny’s political actions beyond his music, using his status as a world-class celebrity to gain visibility to effectively denounce the U.S. ‘s actions In this way, Bad Bunny’s album becomes a transnational site of digital resistance and a project reclaiming identity, celebrating culture and proving that art can serve as a powerful tool of decolonial and cultural expression in the global mainstream.

Previous post

Brussels, 14th of October 2025: how media framing operated at the Office des Étrangers

Previous post

Brussels, 14th of October 2025: how media framing operated at the Office des Étrangers